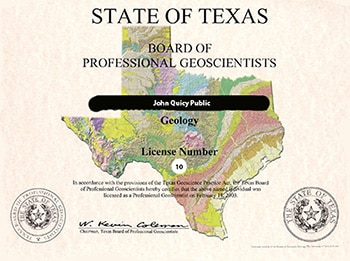

Texas Professional Licensure

Texas Board of Professional Geoscientists has a website, tbpg.state.tx.us, designed to answer all questions relating to licensing Professional Geoscientists in Texas.

Current Disciplinary Actions by the Board (here).

Updated FAQ – February 7, 2018 – (here)

Vigilance is needed during the Texas legislature season to monitor any new legislation that may impact the TBPG and its ability to properly license professional geoscientists in Texas. Henry M. Wise, P.G., President, AIPG Texas Section (and author of the Wise Report) and Matthew R. Cowan, P.G., District IV Representative of AIPG Texas Section have been serving for a number of years as the legislation watchdogs for Texas geoscientists. The Texas Geoscience Council also monitors the Texas State Legislature for any activities that may impact the geosciences in Texas.

How was Geoscientist Licensure established in Texas?

The Texas Geoscience Practice Act (the Act) was enacted in May 2001 upon passage of SB-405 by the 77th Texas Legislature. SB-405 was developed by a coalition of Texas geoscientists, primarily from the environmental, ground-water resources, mining and engineering practice areas. Geoscientists from State agencies and from the oil and gas industry also contributed to the crafting of the Act.

Who must be Licensed to Practice Geoscience in Texas?

Any individual practicing geoscience before the public, including State and local government employees, or anyone holding themselves out to be a geoscientist, must be licensed. Practicing means taking responsible charge of a geoscientific work product. In addition, firms or corporations who engage in the public practice of geoscience must have their geoscientific work performed by or under the supervision of a licensed geoscientist who is responsible for such work.

Are there any Geoscience Practice Areas Exempt from Licensure?

Geoscientific work exempt from licensure includes: work by a subordinate to a licensee if the subordinate does not bear final responsibility for the work; work by an employee or agent of the Federal government acting in their capacity as an employee or agent; work performed to explore for and develop energy and mineral resources, IF the work is done in and for the benefit of private industry; most academic, governmental, and institutional research; teaching of geoscience; and, geoscientific work customarily performed INCIDENTAL to the work of other professions, such as archaeology, geography, oceanography, cartography, etc.

If I work Exclusively in Exploring for and Developing Oil, Gas, or other Energy Resources, do I need to Obtain a License to Continue to Practice?

No, provided the work is only done in and for the benefit of private industry. However, if the work is for a governmental entity in this State, or to comply with a rule established by this State or a political subdivision of this State, you may be required to obtain a license to practice.

What Areas of Geoscience Practice are Subject to Licensure?

By rule, the Board has recognized three geoscience disciplines subject to licensure. These disciplines are: geology, geophysics, and soil science. Geology includes, but is not limited to, such sub-disciplines as: hydrogeology, engineering geology, and environmental geology. License applicants must select one discipline in which to be licensed; however, licensees can practice in any of the recognized disciplines providing they have the training and experience in the sub-discipline. For example, a person with training in soil science should not practice in the field of hydrogeology unless he (or she) has training and experience in hydrogeology. The same applies to soil science and geophysics.

What are the Requirements and Eligibility Criteria for Licensure?

- Application form with personal information and summaries of education and relevant work experience.

- Five or more reference letters, with at least three from qualified geoscientists or other board-acceptable professionals, personally familiar with the applicant’s relevant work experience.

- The application and first-year license fee, set by the Board.

- Graduation from a course of study in one of the Board-recognized geoscience disciplines, with at least 30 semester or 45 quarter credit hours in geoscience. At least 2/3 of these credit hours must be in upper division courses. The Board may accept qualifying work experience in lieu of the formal education requirements only in some circumstance.

- Have a minimum of five, documentable years of qualifying work experience, acquired after award of an undergraduate geoscience degree and under the supervision of a licensed or qualified geoscientist(s) or other professionals acceptable to the Board. Full-time graduate study in a geoscience discipline may qualify for up to two years of work experience credit.

- University-level research in and/or teaching of a geoscience discipline may, at the Board’s discretion, qualify as work experience.

- Pass an exam administered by the Board on the fundamentals and practice of the applicable geoscience discipline. For assistance in preparing for the two tests, see the following ASBOG Handbooks:

1. FUNDAMENTALS OF GEOLOGY (FG) EXAMINATION Should be taken shortly after college graduation.

2. PG CANDIDATE HANDBOOK (2016)

3. PG CANDIDATE HANDBOOK (2014)

See next dates for holding ASBOG examinations in the U.S.: http://tbpg.state.tx.us/ - Other requirements that the Board may adopt by Rule.

Can the Board Waive any or all of the License Eligibility Requirements?

The Board is authorized by the Act to waive any of the eligibility requirements, except the payment of fees. It is the responsibility of an applicant seeking eligibility requirement waivers to demonstrate, to the Board’s satisfaction, justification for such waivers and their qualifications for licensure.

Does the Board have Reciprocal License Arrangements with Other States?

The Act authorizes the Board to enter into reciprocity or comity agreements (mutual recognition of licenses or state-sanctioned professional registrations between states) with other states that regulate the practice of geoscience. For the States with reciprocity, see the TBPG website.

Do Geoscience Licenses/Registrations from other States, Professional Society Certifications, or State Agency-Granted Certifications (e.g: TCEQ’s CAPM Certification) Count Towards License Eligibility?

Not directly. However, applicants are requested to cite such licenses, registrations, and certifications in their application as further evidence of their overall qualifications.

Continuing Education is a Requirement for License Renewal

The Act allows the Board to adopt a requirement of continuing education for license renewal. For the continuing education requirements, see the TBGS web site.

If you have further questions about the Texas geoscientists licensure program, please refer to the Act and rules. Inquiries can also be made via email to the Board at geoscientists@tbpg.state.tx.us or by calling or writing the Board at the address and numbers cited above. In addition, the Board maintains an informational mailing list to which you can subscribe via the Board’s website.

* Disciplinary Actions of the Texas Board of Professional Geoscientists (more).

If anyone would like to have a presentation made to a grouping of geoscientists in your area, either at a company, university, or other location where interested geoscientists are present, please contact one of the following presenters to arrange for a presentation in your area:

Dallas, TX

Kevin Coleman, P.G. – wkc@birch.net

Houston, TX

Matthew R. Cowan, P.G. – wrcowan1@hal-pc.org

Henry M. Wise, P.G., C.P.G. – wise@aipg-tx.org

Dave Rensink, P.G. – dave.rensink@att.net

Michael D. Campbell, P.G., P.H., C.P.G. – mdc@i2mconsulting.com

San Antonio, TX

Ed Miller, P.G. – Egmsat@cs.com

Comparing the Missions of Licensure Boards and Professional Associations

by Robert E. Tepel (reprinted courtesy of the Association of Engineering Geologists from the Sept. 2001 AEG News)

Mission Confusion

Licensed professionals should have a clear understanding of the very different missions of licensure boards and professional associations. Some professionals are unclear about the amount of mission overlap between a professional association and the board that licenses its members, so the topic deserves exploration. In actuality, mission overlap is minimal, and, as we shall see, that is a good situation.

Licensure critics, both inside and outside the profession, often like to paint the picture of identical or broadly overlapping missions, thereby establishing a link that allows them to assert that the professions control the boards that regulate them. This assertion is not valid for today’s geology licensure boards and professional associations.

A Different Sense of Stewardship

The fundamental reason that the missions of licensure boards and professional associations are very different is that each arises from a different sense of stewardship. This is the key to understanding the contrasts in mission. The professional association has a sense of stewardship of the profession it serves, that is, responsibility for archiving its past, hosting its present, and creating its future. A licensure board has no sense of stewardship of the profession it regulates. Instead, the licensure board has a sense of stewardship for the public interest in the practice of the profession it regulates. In other words, the professional association is beholden to its members and the licensure board is beholden to the public.

A professional association or institute may hold, and properly so, that some aspects of stewardship for the public interest in the practice of the profession fall within its purview. Indeed, professional associations are formed in part because members of the profession perceive that they practice under the purview of the public interest, and they want to promote that concept for the public good. However, the public interest aspect of a professional association’s sense of stewardship is but one relatively small element in a multifaceted mission, and it can compete or conflict with other elements. In contrast, the public interest aspect of a licensure board’s sense of stewardship is its entire reason for being.

The State Licensure Board Mission

Simply put, the mission of a licensure board is to protect the public from incompetent or negligent practice by licensees, and from the dangers of unqualified practice by unlicensed people. A licensure board generally has several tools available to use in the pursuit of its mission. Pre-licensure, these would include verifying and evaluating the education and experience of applicants against standards, checking work history and employer, supervisor, or coworker references, and administering a formal examination.

Post-licensure, a board might pursue its mission by requiring continuing demonstration of competence via educational activities, and through a disciplinary program. A board may have an outreach program that sends a message about its mission and goals to the licensed profession, the public, other professionals and their boards, legislators, other regulators, and code writers. That’s about it.

The Professional Association Mission

Simply put, the mission of a professional association is to promote the interests of its members. It does this in a variety of ways. Most geology associations offer educational services such as technical journals, newsletters, meetings, short courses, and field trips. Some may have outreach programs to inform the public of the value of their members’ services, thereby promoting business for their members. Some may have additional outreach to other professional associations. They might participate in multi-association agglomerates or task forces. Any association operating above the subsistence level will guard and promote its members’ business and employment interests by monitoring the legislative, regulatory, code-writing, and standard-setting arenas. This is done to take advantage of opportunities to increase its members business and employment situations, and also to guard against unjustified incursions into its members’ opportunities or their scope of practice.

Most professional associations create business or employment opportunities through the networking climate at meetings and other functions. They might take on an advocacy role and seek opportunities to increase their scope of business practice through legislation or regulation, where justified. The more sophisticated associations monitor the activities of groups that, in pursuit of their own mission, may seek changes that conflict with their members interests, such as other professional associations and public interest or intervenor groups. They watch for initiatives by businesses or alliances that seek to eliminate the burdens of retaining licensed professional consultants, for example by easing or eliminating regulations requiring geologic reports. (All of this takes money and a financially starved association can not fulfill its potential in these endeavors).

Mutually Supportive Mission Elements

A professional association may support licensure in concept and a licensure board in practice because it believes that licensure operates in the public interest, and the association has expertise that will support the board as it pursues its mission. This is a valid exercise in altruism. On a less lofty plane, a professional association may find itself supporting a licensure board in the give and take of political life. Here are some examples. Labor organizations (for example, government employee unions) may try to increase their members’ well-being by reducing licensure qualification criteria (or opposing new criteria that are more stringent). Their desire is to open the path for faster promotion for their members, or to raise the ceiling on the career path. A regulatory agency may seek to eliminate the need for a class of reports to be prepared by licensees only. This reduces its workload in verifying the licensee’s signatures and the validity of their licenses, as well as the expense of hiring licensed employees to review the work submitted by licensees. In supporting strong licensure board standards or regulations in these cases, the professional association can recognize that its mission and the licensure board’s mission are mutually supportive.

A professional association may support licensure in concept and a licensure board in practice acting in its members’ interests. A license, after all, is a credential that has value to the licensed professional. Of course, a professional association may seek to improve the public safety and health by promoting laws, regulations, and codes that require use of the profession’s services. In so doing, it must be able to demonstrate a benefit that is worth the cost. A professional association may work cooperatively with regulatory agencies to jointly sponsor conferences or classes. The shared mission benefit of this activity is that the regulators and the regulated work from a common and advanced knowledge base. This serves the public interest and the members’ interest.

Mission Conflicts

The mission of a licensure board can conflict with the mission of an association representing the regulated profession. A common conflict is the board’s impositions of reporting paperwork, new liability, or time-consuming and expensive regulation (such as a new continuing education requirement) on the practicing professionals. Recently, some consulting geologists in California felt put upon when the Board for Geologists and Geophysicists established a requirement that their license number appear on business cards, letterhead, advertising (including telephone directory listings), and Statements of Qualifications. No doubt, this is burdensome to many consulting firms, but from the board’s standpoint, the overriding public interest is to establish readily traceable responsibility for the professional work. This requirement also helps to educate the public (consumers) that there is such a thing as professional licensure for geologists, a legitimate Board goal.

Other conflicts might arise from the board’s turn-around time in evaluating licensure applications, reporting examination scores, or processing requests for “reciprocity.” These conflicts arise because the members of the profession want fast service from the board and unfettered practice. Another conflict arises if a board does not or can not implement an effective disciplinary program. Professional associations are image-conscious and would like to kick the scoundrels out and re-educate the negligent.

Some professionals expect the board to promote the profession to the public, or to protect their scope of practice solely on a “turf” basis. These activities are definitely not within the board’s mission. They are solely within the mission of the professional association.

Special Note: Opposition to Licensing in Texas?

An oil and gas geologist in 1994 published a Commentary in the Bulletin of the Houston Geological Society that was very critical of the registration of geologists. See (McLead Commentary-1994). It should be read by all Texas geologists.

Mission Pseudo-Similarities

A licensure board may be perceived as a surrogate for a professional association when it defends laws or regulations that confirm practice rights on the regulated profession. It may be similarly perceived if it promotes laws or regulations that expand practice rights enjoyed by the regulated profession. Appearances aside, the true basis for such activities is found in the board’s mission to protect the public from unqualified or incompetent practitioners. While collateral benefits to the profession may be apparent to the board, they are not and can not be any part of the driving force of its efforts. Politically astute boards and their administrators are well aware of this. They will not undertake any initiative burdened by an easily challenged overflow benefit to the profession.

The profession may support the board in its efforts to defend, enforce, clarify, or expand practice rights, first out of altruism and second because the public benefits result in member benefits. In my opinion the geology licensure process has been and is quite free of self-serving motives on the part of supporting professionals and their associations.

Mission Symbiosis

A professional association might promote board regulations that benefit it as well as its members and the public. Example: the promotion (or even grudging acceptance) of a continuing education requirement that includes a mechanism by which the association can be recognized as a qualified provider of continuing education, thereby benefiting the association’s member service image and cash flow. An association might be interested in setting the board’s continuing education requirements at a modest level so it can establish its own, slightly higher, annual education hour requirements. In this case, the association and its members can advertise to the public that “our members have to meet higher standards than the typical licensee.” (This example comes from the real world, but not geology. It could be applied in geology, however).

Conclusion

Licensure boards have a simple mission with narrow focus: to protect the public, operating within the bounds of their legal authority, from incompetent or negligent practice by licensees, and from the dangers of unqualified practice by unlicensed people. Professional associations have a more complex mission with a different focus, serving their members’ interests. The missions are not congruent. They are mutually supportive at times, but are not identical because each organization operates from a unique sense of stewardship and mission.

Afterword: Internal Conflicts of Mission in Certifying Professional Associations

The above discussion shows that the missions of licensure boards and professional associations are fundamentally different, share common goals only rarely, and occasionally are in conflict. Conflicts that arise are resolved in the open forum of public licensure board meetings, where all interested parties (including the public) receive notice and can participate. This is healthy because the conflicts are made known in a public forum, and are seen as resulting from the differing missions of two separate organizations, one a regulatory agency and one a business league.

In contrast, consider the question of potential or real conflicts internalized within a certifying professional association. How can a professional association that claims its certification program protects the public resolve the potential conflict between the putative mission of its certifying body (to protect the public) and its overall mission to serve and promote its members’ interests?

Avoiding conflicts, or the appearance of conflicts, within a certifying professional association or institute is possible if established standards are met. The prime resource is the “Standards for Accreditation of National Certification Organizations” of the National Commission for Certifying Agencies (NCCA), a part of the National Organization for Competency Assurance (NOCA). These standards in essence require that, if a certifying body is part of a parent organization, it shall operate with administrative independence and be free from pressure or interference from the parent organization. The standards (pages xii – xx in Browning and others, 1996), are extensive. They provide for the inclusion of a public member on the certification panel, for example. The standards are in revision at this writing. A draft of the proposed new standards is available on the NOCA website, www.noca.org. I am unaware of any professional geoscience association or institute certification program that conforms fully to the 1996 NCCA Guidelines and has received NOCA accreditation.

Reference

Browning, Anne H., Bugbee, Alan C., Jr., and Mullins, Meredith A., editors, 1996, Certification, a NOCA Handbook, National Organization for Competency Assurance, Washington DC, 302 p.

In The News

Sponsors of the AIPG-TX GEODAYZ Training Program

2022

2018